It is important to have some basic information regarding protection of your family’s possessions in case of fire, flood, earthquake, etc. Knowing how to prepare for such situations is crucial when you only have a few minutes to leave your residence or workplace and want to know what to take.

Your concerns may be about whether to gather works of art because of their value or family documents and photographs because of their sentimental and historical importance. No matter how many or few of these treasures you have, there are some basic steps to take to protect letters, legal documents, genealogy charts, heirlooms, photographs, and rare books. They will also help you get organized in general. Here are some tips to help you be better prepared:

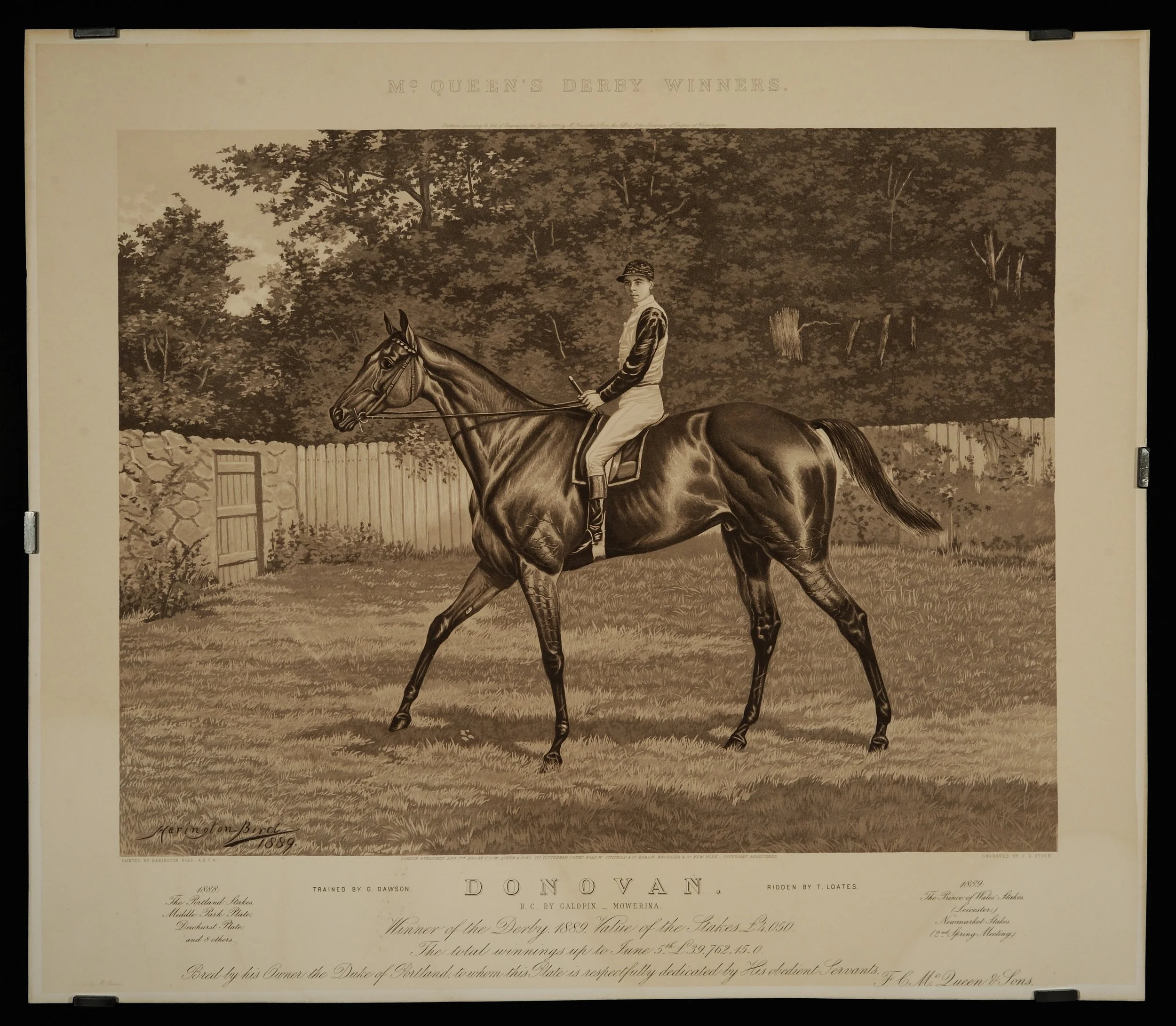

Sort through any valuable items and, to the extent possible, photograph treasured items and make photocopies of documents. The duplicates should be placed in a separate box from the originals and preferably stored at another location (a relative’s house or workplace, for example). Alternatively, digital images and scans can be saved to an external storage device, like a hard drive or USB drive, and kept in a different location for back-up.

Keep photos in archival albums that are easy to grab, such as in a bookcase or storage box that is accessible. Place labels on the outside that identify the contents, written in pencil or permanent pen ink. Graphite is stable in water. Felt-tipped pens and markers will bleed with moisture and fade over time.

Keep storage boxes away from water pipes (water heaters too) that could break and flood on your treasured items, causing water and mold damage.

For framed art and documents, make sure hanging hooks and wires are strong, oversized and well anchored into the wall or moulding. I can’t tell you how many artworks and frames require repair because the wires give way or an earthquake shakes them loose. When they fall it can be onto a corner of a table or through a vase. Acrylic glazing is preferable to glass because it won’t shatter and damage the contents of the frame.

You may need supplemental insurance for earthquakes. Make sure your homeowner’s policy covers your contents. Heirlooms should not require a Fine Arts rider, but should fall under your regular homeowner’s policy. You will still need photos and values for a claim, and for important items that have been purchased, a copy of the sales receipt with date, description and price is important to have. For a quick “visual inventory” of your home’s contents, make a video.

If you have possessions that you don’t want to lose, spend a little time using available resources that can help with measures to prevent damage before a disaster (or in normal circumstances):

Schultz, Arthur, ed. Caring for Your Collections: Preserving and Protecting your Art and other Collectibles. Harry Abrams publication.

Long, Jane & Richard. Caring for Your Family Treasures. Heritage Preservation, Harry Abrams publication, 2000 paperback.